Thamil History

The Thamillpeople, also known as Thamilar (Thamill: தமிழர், romanized: Thamilḻar, pronounced [t̪amiɻaɾ] in the singular or தமிழர்கள், Thamilḻarkaḷ, [t̪amiɻaɾɡaɭ] in the plural), Thamillians,or simply Tamils (/ˈtæmɪlz, ˈtɑː-/ TAM-ilz, TAHM-), are a ethnolinguistic group who natively speak the Thamill language and trace their ancestry mainly to India's southern state of Thamill Nadu, the union territory of Puducherry, and to Sri Lanka.

The Thamill language is one of the world's longest-surviving classical languages, with over 2000 years of Thamill literature, including the Sangam poems, which were composed between 300 BCE and 300 CE. People who speak Thamillas their mother tongue and are born in Thamill clans are considered Tamils.

Tamils constitute 5.9% of the population in India (concentrated mainly in Thamill Nadu and Puducherry), 15% in Sri Lanka (excluding Eelam Moors), 7% in Malaysia, and 5% in Singapore.

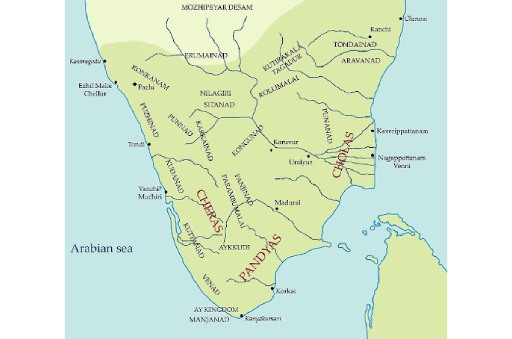

From the 4th century BCE, urbanisation and mercantile activity along the western and eastern coasts of Thamillakam what is today Kerala and Thamill Nadu led to the development of four large Thamill empires, the Cheras, Cholas, Pandyas, and Pallavas and a number of smaller states, all of whom were warring amongst themselves for dominance.

The Jaffna Kingdom, inhabited by Eelam Tamils, was once one of the strongest kingdoms of Sri Lanka and controlled much of the north of the island.

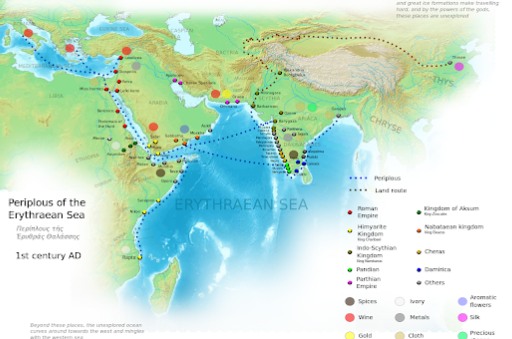

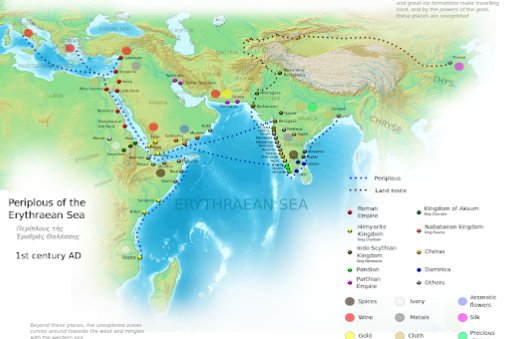

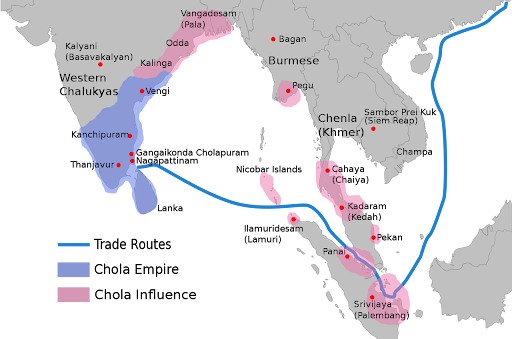

Tamils were noted for their influence on regional trade throughout the Indian Ocean. Artefacts marking the presence of Roman traders demonstrate that direct trade was active between Ancient Rome and Southern India, and the Pandyas were recorded as having sent at least two embassies directly to the Roman Emperor Augustus in Rome. The Pandyas and Cholas were historically active in Sri Lanka.

The Chola dynasty successfully invaded several areas in southeast Asia, including the powerful Srivijaya and the city-state of Kedah.

Medieval Thamillguilds and trading organizations like the Ayyavole and Manigramam played an important role in Southeast Asian trading networks.

Pallava traders and religious leaders travelled to Southeast Asia and played an important role in the cultural Indianisation of the region. Scripts brought by Thamill traders to Southeast Asia, like the Grantha and Pallava scripts, induced the development of many Southeast Asian scripts such as Khmer, Javanese, Kawi, Baybayin, and Thai.

Thamill visual art is dominated by stylized Temple architecture in major centres and the productions of images of deities in stone and bronze. Chola bronzes, especially the Nataraja sculptures of the Chola period, have become notable symbols of Hinduism. A major part of Thamill performing arts is its classical form of dance, the Bharatanatyam, whereas the popular forms are known as Koothu. Classical Thamill music is dominated by the Carnatic genre, while gaana and dappankuthu are also popular genres.

Thamill is an official language in Sri Lanka and Singapore. In 2004, Thamill was the first of six to be designated as a classical language of India.

The vast majority of Thamill people are Hindus and many follow a particular way of religious practice that includes the veneration of a plethora of village deities and ancient Thamill gods.

A smaller number are Christians and Muslims, and a small Jain community survives from the classical period as well.

A smaller number are Buddhists. Thamill cuisine is informed by varied vegetarian and non-vegetarian items, usually spiced with locally available spices.

English historian and broadcaster Michael Wood called the Tamils the last surviving classical civilization on Earth, because the Tamils have preserved substantial elements of their past regarding belief, culture, music, and literature despite the influence of globalization.

Grey pottery with engravings, Arikamedu, 1st century CE

Etymology

It is unknown whether the term Tamiḻlar and its equivalents in Prakrit such as Damela, Dameda, Dhamila, and Damila was a self-designation or a term denoted by outsiders. Epigraphic evidence of an ethnicity termed as such is found in ancient Sri Lanka, where a number of inscriptions have come to light dating from the 2nd century BCE mentioning Damela or Dameda persons. The well-known Hathigumpha inscription of the Kalinga ruler Kharavela refers to a T(ra)mira samghata (Confederacy of Thamill rulers) dated to 150 BCE. It also mentions that the league of Thamill kingdoms had been in existence 113 years before then. In Amaravati (located in present-day Andhra Pradesh) is an inscription referring to a Dhamila-vaniya (Thamill trader) datable to the 3rd century CE.

In the Buddhist Jataka story known as Akiti Jataka there is a mention of a Damila-rattha (Thamill dynasty). There were trade relationship between the Roman Empire and Pandyan Empire. As recorded by the Hellenistic Greek historian and geographer Strabo, the Roman Emperor Augustus of Rome received at Antioch an ambassador from a king called Pandyan of Dramira.

Hence, it is clear that by at least 300 BCE, the ethnic identity of Tamils was formed as a distinct group. Thamilḻar is etymologically related to Tamil, the language spoken by Thamill people. Southworth suggests that the name comes from tam-miz > tam-iz - "self-speak", or "our own speech".

Zvelebil suggests an etymology of tam-iz, with tam meaning "self" or "one's self", and "-iz" having the connotation of "unfolding sound". Alternatively, he suggests a derivation of tamiz < tam-iz < *tav-iz < *tak-iz, meaning in origin "the proper process (of speaking)".

History

Prehistoric period

Possible evidence indicating the earliest presence of Thamill people in modern-day Thamill Nadu are the megalithic urn burials, dating from around 1500 BCE and onwards, which have been discovered at various locations in Thamill Nadu, notably in Adichanallur in Thoothukudi District which conform to the descriptions of funerals in classical Thamill literature.

Various legends became prevalent after the 10th century CE regarding the antiquity of the Thamill people. According to Iraiyanar Agapporul, a 10th/11th century annotation on the Sangam literature, the Thamill country extended southwards beyond the natural boundaries of the Indian peninsula comprising 49 ancient nadus (divisions). The land was supposed to have been destroyed by a deluge. The Sangam legends also alluded to the antiquity of the Thamill people by claiming tens of thousands of years of continuous literary activity during three Sangams.

There are literary, archaeological, epigraphic and numismatic sources of ancient Thamill history. The foremost among these sources is the Sangam literature, generally dated to 5th century BCE to 3rd century CE. The poems in Sangam literature contain vivid descriptions of the different aspects of life and society in Thamillakam during this age; scholars agree that, for the most part, these are reliable accounts. Greek and Roman literature, around the dawn of the Christian era, give details of the maritime trade between Thamillakam and the Roman empire, including the names and locations of many ports on both coasts of the Thamill country. There are evidences as could be seen comparing standard forms of Sumerian literature and those recovered through present form of Tamil, for example the word for father in Sumerian transliteration is given as, "a-ia" that could easily be compared with Thamill word, "ayya".

This also places ancient form of Thamill to early Sumerian period, say as ancient as 3500 BC. Archaeological excavations of several sites in Thamill Nadu and Kerala have yielded remnants from the Sangam era, such as different kinds of pottery, pottery with inscriptions, imported ceramic ware, industrial objects, brick structures and spinning whorls. Techniques such as stratigraphy and paleography have helped establish the date of these items to the Sangam era. The excavated artifacts have provided evidence for existence of different economic activities mentioned in Sangam literature such as agriculture, weaving, smithy, gem cutting, building construction, pearl fishing and painting.

Inscriptions found on caves and pottery are another source for studying the history of Tamilakam. Writings in Tamil-Brahmi script have been found in many locations in Kerala, Thamill Nadu, Sri Lanka and also in Egypt and Thailand mostly recording grants made by the kings and chieftains. References are also made to other aspects of the Sangam society. Coins issued by the Thamill kings of this age have been recovered from river beds and urban centers of their kingdoms. Most of the coins carry the emblem of the corresponding dynasty on their reverse, such as the bow and arrow of the Cheras; some of them contain portraits and written legends helping numismatists assign them to a certain period.

Classical period

Ancient Thamills had three monarchical states, headed by kings called "Vendhar" and several tribal chieftainships, headed by the chiefs called by the general denomination "Vel" or "Velir". Still lower at the local level there were clan chiefs called "kizhar" or "mannar". The Thamill kings and chiefs were always in conflict with each other, mostly over territorial hegemony and property.

The royal courts were mostly places of social gathering rather than places of dispensation of authority; they were centres for distribution of resources. Ancient Thamill Sangam literature and grammatical works, Tolkappiyam; the ten anthologies, Pattuppāṭṭu; and the eight anthologies, Eṭṭuttokai also shed light on ancient Thamill people. The kings and chieftains were patrons of the arts, and a significant volume of literature exists from this period.

The literature shows that many of the cultural practices that are considered peculiarly Thamill date back to the classical period.

Culture and tradition of old thamills can be well known by the text Purananuru which mainly talks about public life and explains how people lived in Ancient Thamill Nadu. The text states that several kings believed that Vedic Sacrifices help in upholding righteousness and brings happiness to the country. Vedas were considered as the book of Righteousness and did not speak about materialism and Cruelness. The text also explains death rituals and concept of Re-birth. after a person is dead all his family and friends weep and cry, if a husband is dead the wife hits her chest and cries and the bangles break. Only men go to cremation ground and the women clean the house and apply cow dung to the front yard of the house. The son or some other relative give the body to the person who performs Ritual rights, further the person performs good rituals with the family members to the corpse and finally gives rice to the corpse, The text explains the significance of rice fed by the person to the corpse, and later the body is burnt. If the wife dies the men feels so sad and also feels to die, he does not want to sleep on the bed of rock and instead sleep in the bed of fire and same rituals are performed. People who perform good deeds in this birth gets a better birth in his next life, if a king was so good and generous, The king of Heaven Indra who holds the Vajra welcomes him to Heaven with pleasure. If a person lives a normal life he goes to the world of dead (Probably Pitru Lokam). After all the rituals a Nadukal is kept for the dead king and is worshiped by people. Some poets consider Nadukal as the only god.

Agriculture was important during this period, and there is evidence that networks of irrigation channels were built as early as the 3rd century BCE. Internal and external trade flourished, and evidence of significant contact with Ancient Rome exists. Large quantities of Roman coins and signs of the presence of Roman traders have been discovered at Karur and Arikamedu. There is evidence that at least two embassies were sent to the Roman Emperor Augustus by Pandya kings. Potsherds with Thamill writing have also been found in excavations on the Red Sea, suggesting the presence of Thamillmerchants there. An anonymous 1st century traveller's account written in Greek, Periplus Maris Erytraei, describes the ports of the Pandya and Chera kingdoms in Damirica and their commercial activity in great detail. Periplus also indicates that the chief exports of the ancient Tamils were pepper, malabathrum, pearls, ivory, silk, spikenard, diamonds, sapphires, and tortoiseshell.

The classical period ended around the 4th century CE with invasions by the Kalabhra, referred to as the kalappirar in Thamill literature and inscriptions. These invaders are described as 'evil kings' and 'barbarians' coming from lands to the north of the Thamill country, but modern historians think they could have been hill tribes who lived north of Thamill country. This period, commonly referred to as the Dark Age of the Thamill country, ended with the rise of the Pallava dynasty.

Sangam

By far, the most important source of ancient Thamill history is the corpus of Thamill poems, referred to as Sangam literature, generally dated from the last centuries of the pre-Christian era to the early centuries of the Christian era. It consists of 2,381 known poems, with a total of over 50,000 lines, written by 473 poets. Each poem belongs to one of two types: Akam (inside) and Puram (outside). The akam poems deal with inner human emotions such as love and the puram poems deal with outer experiences such as society, culture and warfare. They contain descriptions of various aspects of life in the ancient Thamill country. The Maduraikkanci by Mankudi Maruthanaar contains a full-length description of Madurai and the Pandyan country under the rule of Nedunj Cheliyan III.

The Netunalvatai by Nakkirar contains a description of the king’s palace. The Purananuru and Akanaṉūṟu collections contain poems sung in praise of various kings and also poems that were composed by the kings themselves. The Sangam age anthology Pathirruppaththu provides the genealogy of two collateral lines for three or four generations of the Cheras, along with describing the Chera country, in general. The poems in Ainkurnuru, written by numerous authors, were compiled by Kudalur Kizhar at the instance of Chera King Yanaikkatcey Mantaran Ceral Irumporai.The Chera kings are also mentioned in other works such as Akanaṉūṟu, Kuruntokai, Natṟiṇai and Purananuru. The Pattinappaalai describes the Chola port city of Kaveripumpattinam in great detail. It mentions Eelattu-unavu – food from Eelam – arriving at the port. One of the prominent Sangam Thamill poets is known as Eelattu Poothanthevanar meaning Poothan-thevan (proper name) hailing from Eelam mentioned in Akanaṉūṟu: 88, 231, 307; Kurunthokai: 189, 360, 343 and Naṟṟiṇai: 88, 366.

The historical value of the Sangam poems has been critically analysed by scholars in the 19th and 20th centuries. Sivaraja Pillay, a 20th-century historian, while constructing the genealogy of ancient Thamill kings from Sangam literature, insists that the Sangam poems show no similarities with ancient Puranic literature and medieval Thamill literature, both of which contain, according to him, fanciful myths and impossible legends. He feels that the Sangam literature is, for the most part, a plain unvarnished tale of the happenings of a by-gone age. Scholars like Dr. Venkata Subramanian, Dr. N. Subrahmanian, Dr. Sundararajan and J.K. Pillay concur with this view. Noted historian K.A.N. Sastri dates the presently available Sangam corpus to the early centuries of the Christian Era. He asserts that the picture drawn by the poets is in obedience to literary tradition and must have been based on solid foundation in the facts of contemporary life; he proceeds to use the Sangam literature to describe the government, culure and society of the early Pandyan kingdom.Kanakalatha Mukund, while describing the mercantile history of Thamillakam, points out that the heroic poetry in Sangam literature often described an ideal world rather than reality, but the basic facts are reliable and an important source of Thamill history. Her reasoning is that they have been supported by archaeological and numismatic evidence and the fact that similar vivid descriptions are found in works by different poets. Dr. Husaini relies on Sangam literature to describe the early Pandyan society and justifies his source by saying that some of the poetical works contain really trustworthy accounts of early Pandyan kings and present facts as they occurred, though they never throw much light about the chronology of their rule.

Among the critics of using Sangam literature for historical studies is Herman Tieken, who maintains that the Sangam poems were composed in the 8th or 9th century and that they attempt to describe a period much earlier than when they were written. Tieken's methodology of dating Sangam works has been criticized by Hart, Ferro-Luzzi, and Monius. Robert Caldwell, a 19th-century linguist, dates the Sangam works to a period that he calls the Jaina cycle which was not earlier than the 8th century; he does not offer an opinion on the historical value of the poems. Kamil Zvelebil, a Czech indologist, considers this date quite impossible and says that Caldwell's choices of work are whimsical. Champakalakshmi states that since the Sangam period is often stretched from 300 BCE to 300 CE and beyond, it would be hazardous to use the Sangam works as a single corpus of source for the entire period.

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, the Sangam poems were created between the 1st century BCE and 4th century CE and many of them are free from literary conceits.The Macropaedia mentions that the historical authenticity of sections of Sangam literature has been confirmed by archaeological evidence.

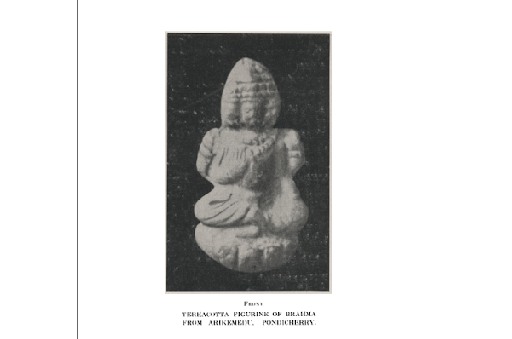

Archaeology

According to Abraham, the Sangam era corresponds roughly to the period 300 BCE–300 CE, based on archaeology. Many historical sites have been excavated in Thamill Nadu and Kerala, many of them in the second half of the 20th century. One of the most important archaeological sites in Thamill Nadu is Arikamedu, located 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) south of Pondicherry. According to Wheeler, it was an Indo-Roman trading station that flourished during the first two centuries CE. It has been suggested that Arikamedu was first established as a settlement c. 250 BCE and lasted until 200 CE. Kodumanal and Perur, villages on the banks of the Noyyal river in Coimbatore district, were situated on the ancient trade route between Karur and the west coast, across the Palghat gap on the Western Ghats. Both sites have yielded remains belonging to the Sangam age. Kaveripumpattinam, also known as Puhar or Poompuhar, is located near the Kaveri delta and played a vital role in the brisk maritime history of ancient Thamillakam. Excavations have been carried out both on-shore and off-shore at Puhar and the findings have brought to light the historicity of the region. The artefacts excavated date between 300 BCE and early centuries CE. Some of the off-shore findings indicate that parts of the ancient city may have submerged under the advancing sea or tsunami, as alluded to by the Sangam literature. Korkai, a port of the early Pandyas at the Tamraparani basin, is now located 7 km inland due to the retreating shoreline caused by sediment deposition. Alagankulam, near the Vaigai delta, was another port city of the Pandyas and an archaeological site that has been excavated in the recent years. Both the Pandyan ports have provided clues about local occupations, such as pearl fishing. Other sites that have yielded remnants from the Sangam age include Kanchipuram, Kunnattur, Malayampattu and Vasavasamudram along the Palar river; Sengamedu and Karaikadu along the Pennar river; Perur, Tirukkampuliyur, Alagarai and Urayur along the Kaveri river. These excavations have yielded different varieties of ceramics such as black and red ware, rouletted ware and Russet coated ware, both locally made and imported kinds. Many of the pottery sherds contain Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions on them, which have provided additional evidence for the archaeologist to date them. Other artifacts such as brick walls, ring wells, pits, industrial items, remains of seeds and shells provide clues about the nature of the settlements and the other aspects of life during the Sangam age. Archaeologists agree that activities best illustrated in the material records of Tamilakam are trade, hunting, agriculture and crafts.

Economic activity evidence

Archeological evidence for agriculture in the Sangam age has been retrieved from sites such as Mangudi, Kodumanal and Perur, which have yielded charred remains of seeds of crops like rice, millets including pearl millets, pulses and cotton. It has been deduced that agriculture most likely involved dry farming, with additional irrigation for cotton and rice; mixed cropping seems to have been undertaken to replenish the nitrogen in the soil—this also suggests a spread of labour and knowledge of different sowing and harvesting techniques. The presence of cotton seeds indicates the production of a crop aimed at craft production, which is also attested by finds of cotton and spindle whorls at Kodumanal.

Remains of structures that resemble an artificial water reservoir have been located at different sites. In Arikamedu, a few terracotta ring-wells were found at the bottom of the reservoir; it has been suggested that the ring wells were to assure the supply of water during the dry season.

A research survey at Kodumanal has unearthed the remains of an ancient blast furnace, its circular base distinguishable by its white colour, probably the result of high temperature. Around the base, many iron slags, some with embedded burnt clay, vitrified brick-bats, many terracotta pipes with vitrified mouths and a granite slab, which may have been the anvil, have been recovered. Absence of potsherds and other antiquities has suggested that the smelting place was located outside the boundary of habitation. More furnaces were discovered at the same site with burnt clay pieces with rectangular holes. The pieces were part of the furnace wall, the holes designed to allow a natural draught of air to pass through evenly into the furnace. Many vitrified crucibles were also recovered from this site; one of them notable because it was found in an in situ position. Evidence of steel making is also found in the crucibles excavated at this site. In addition to iron and steel, the metallurgy seems to have possibly extended to copper, bronze, lead, silver and gold objects. At Arikamedu, there were indications of small-scale workshops containing the remains of working in metal, glass, semiprecious stones, ivory and shell. Kodumanal has yielded evidence for the practice of weaving, in the form of a number of intact terracotta spindle whorls pierced at the centre by means of an iron rod, indicating the knowledge of cotton spinning and weaving. To further strengthen this theory, a well preserved piece of woven cotton cloth was also recovered from this site. Dyeing vats were spotted at Arikamedu.

Many brick structures have been located at Kaveripumpattinam during on-shore, near shore and off-shore explorations; these provide proof for building construction during Sangam age. The on-shore structure includes an I-shaped wharf and a structure that looks like a reservoir. The wharf has a number of wooden poles planted in its structure to enable anchorage of boats and to facilitate the handling of cargo. Among other structures, there is a Buddhist vihara with parts of it decorated using moulded bricks and stucco. Near shore excavations yielded a brick structure and a few terracotta ring wells. Off-shore explorations located a fifteen course brick structure, three courses of dressed stone blocks, brick bats and pottery. At Arikamedu, there were indications of a structure built substantially of timber, possibly a wharf. Conical jars that could have been used for storing wine and oil have been found near structures that could have been shops or storage areas. Evidence of continued building activity are present at this site, with the most distinctive structures being those of a possible warehouse, dyeing tanks and lined pits.

Kodumanal was popular for the gem-cutting industry and manufacture of jewels. Sites bearing natural reserves of semi-precious stones such as beryls, sapphire and quartz are located in the vicinity of Kodumanal. Beads of sapphire, beryl, agate, carnelian, amethyst, lapis lazulli, jasper, garnet, soapstone and quartz were unearthed from here. The samples were in different manufacturing stages – finished, semi-finished, drilled and undrilled, polished and unpolished and in the form of raw material. Chips and stone slabs, one with a few grooved beads, clearly demonstrate that these were manufactured locally at Kodumanal. Excavations at Korkai have yielded a large number of pearl oyesters at different levels, indicating the practice of the trade in this region. Some of the objects excavated from Kodumanal show a lot of artistic features such as paintings on the pottery, engravings on the beads, hexagonal designs on beads, inlay work in a tiger figurine and engraved shell bangles. More than ten designs are noticed in the paintings and bead etchings.

There are remnants of many of the items imported from and exported to the Roman empire, at Arikamedu. Imported items recovered from here include ceramics such as amphorae and sherds of Arretine ware, glass bowls, Roman lamps, a crystal gem and an object resembling a stylus. Artifacts that may have been meant for export include jewellery, worked ivory, textiles and perhaps leather or leather-related products. Similar looking ornaments have been recovered from Arikamedu and Palatine Hill in Rome, further confirming that this site was a leading trade center. The Pandyan port city Alagankulam has yielded a rouletted pottery ware that bears the figure of a ship on the shoulder portion. This figure is very similar to a finding reported from Ostia, an ancient port of the Romans. Wharf-like structures found at many port cities indicate that they might have been used as docks. Based on marine explorations of various port-sites, it has been suggested that stone anchors may have been used since as early as the 3rd century BCE.

Cave

The 2nd and 13th rock edicts of Ashoka (273–232 BCE) refers to the Pandyas, Cholas, Cheras and the Satiyaputras. According to the edicts, these kingdoms lay outside the southern boundary of the Mauryan Empire. The Hathigumpha inscription of the Kalinga King, Kharavela, (c. 150 BCE) refers to the arrival of a tribute of jewels and elephants from the Pandyan king. It also talks about a league of Thamillkingdoms that had been in existence 113 years before then. The earliest epigraphic records of the Thamillcountry in ThamillNadu were found in Mangulam village near Madurai. The cave inscriptions, deciphered in 1966, have been dated to the 2nd century BC and record the gift of a monastery by Pandyan king Nedunj Cheliyan to a Jain monk. These inscriptions are also the oldest Jain inscriptions in South India and among the oldest in all of India. References to Sangam age Chera dynasty are found in Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions of 3rd century CE found on rocks in Edakal hill in Wynad district of Kerala. The ancient port city of Thondi is mentioned in inscriptions found in Kilavalavu village near Madurai. The early part of the 20th century saw the discovery of about 39 inscriptions in a dozen locations, all near Madurai. The most significant of these were the ones at Alagarmalai and Sittannavasal. The Alagarmalai inscriptions, dated to the 1st century BCE, record the endowments made by a group of merchants from Madurai. Another set of inscriptions from the 2nd century CE, found at Pugalur village near Karur, document the construction of a rock shelter by a Chera king of the Irumporai line for a Jain monk, Cenkayapan. Cave inscriptions at Arachalur, dated to the 4th century, provide evidence for the cultivation of music and dance in the Thamillcountry. One of the earliest inscriptional evidence of the chieftains of the Sangam age was found at Jambai, a village near the town of Tirukkoyilur in Villupuram district of ThamillNadu. These inscriptions belonging to the 1st century CE record the grants made by the chieftain Atiyaman Netuman Anci who ruled from Takatur. According to epigraphist I. Mahadevan, there were some reservations initially, about the linguistic details in the inscriptions, but further investigations have confirmed their authenticity. Inscriptions from the 2nd century CE found at Mannarkoil village in Tirunelveli district contain a reference to a katikai, which could mean an assembly of learned persons or an institution of higher learning. An inscription belonging to the early Cholas has been discovered near Tiruchirappalli and has been dated between the 2nd and 4th century. An analysis of the geographical sites of these cave inscriptions points to the possibility of the Tamil-Brahmi script having been created at Madurai around the 3rd century BCE and its disseminations to other parts of Thamillcountry thereafter.

Pottery

Tissamaharama ThamillBrahmi inscriptions

Inscriptions on pottery, written in Tamil-Brahmi, have been found from about 20 archaeological sites in ThamillNadu. Using methods such as stratigraphy and palaeography, these have been dated between the 2nd century BCE and 3rd century CE. Also found in present-day Andhra Pradesh and Sri Lanka, similar inscriptions in Tamil-Brahmi have been found outside the ancient Thamillcountry in Thailand and the Red Sea coast in Egypt. Arikamedu, the ancient port city of the Cholas, and Urayur and Puhar, their early capitals, have yielded several fragmentary pottery inscriptions, all dated to the Sangam age. Kodumanal, a major industrial center known for the manufacture of gems during this period, had remains of pottery with inscriptions in Tamil, Prakrit and Sinhala-Prakrit. Alagankulam, a thriving sea port of the early Pandyas, has yielded pottery inscriptions that mention several personal names including the name of a Chera prince. One of the pottery sherds contained the depiction of a large Roman ship. Many other ancient sites such as Kanchipuram, Karur, Korkai and Puhar have all yielded pottery with inscriptions on them. Outside of ThamillNadu and Kerala, inscriptions in Tamil-Brahmi have been found in Srikakulam district in Andhra Pradesh, Jaffna in modern Sri Lanka, ancient Roman ports of Qusier al-Qadim and Berenike in Egypt. The 2nd century BCE potsherds found in excavations in Poonagari, Jaffna, bear Thamillinscriptions of a clan name – vēḷāṉ, related to velirs of the ancient Thamillcountry. The inscriptions at Berenike refer to a Thamillchieftain Korran.

Other

The Thiruparankundram inscription found near Madurai in ThamillNadu and dated on palaeographical grounds to the 1st century BCE, refers to a person as a householder from Eelam (Eela-kudumpikan). It reads: erukatur eelakutumpikan polalaiyan – "Polalaiyan, (resident of) Erukatur, the husbandman (householder) from Eelam. Apart from caverns and pottery, Tamil-Brahmi writings are also found in coins, seals and rings of the Sangam age. Many of them have been picked up from the Amaravathi river bed near Karur. A smaller number of inscribed objects have been picked up from the beds of other rivers like South Pennar and Vaigai. An oblong piece of polished stone with Tamil-Brahmi inscription has been located in a museum in the ancient port city of Khuan Luk Pat in southern Thailand. Based on the inscription, the object has been identified as a touchstone (uraikal) used for testing the fitness of gold. The inscription is dated to 3rd or 4th century.

Polity

Epigraphy provides an account of various aspects of Sangam polity and has been used to verify some of the information provided by sources such as literature and numismatics. The names of various kings and chieftains occurring in the inscriptions include Nedunj Cheliyan, Peruvaluthi, Cheras of the Irumporai family, Tittan, Nedunkilli, Adiyaman, Pittan and Korrantai. References to administration includes the chiefs, superintendents, titles of ministers, palace of merchants and the village assembly. Religious references to Buddhist and Jain monks are found frequently, which have provided valuable information explaining the spread of those religions in Tamilakam. Brief mentions of various aspects of the Sangam society such as agriculture, trade, commodities, occupations, the social stratification, flora, fauna, music and dance, names of cities and names of individuals are also found in the inscriptions.

Coins

Another important source of studying ancient Thamill history are the coins that have been found in recent years in the excavations, megaliths, hoards and surface. The coins belonging to the Sangam age, found in Thamill Nadu are generally classified into three categories. The first category consists of punch-marked coins from Magadha (400 BCE–187 BCE) and the Satavahanas (200 BCE–200 CE). The second category is made up of coins from the Roman Empire dated from 31 BCE to 217 CE, coins of Phoenicians and Seleucids and coins from the Mediterranean region (c. 300 BCE). The third category of Sangam age Thamill coins are the punch-marked silver, copper and lead coins dated 200 BCE–200 CE and assigned to the Sangam age Thamill kings. The coins belonging to the first two categories mostly attest to the trading relationships that the Thamill people had with the kingdoms of northern India and the outside world. But they do not offer much information regarding the Sangam age Thamill polity. Those in the third category provide direct testimony to the existence of ancient Thamillkingdoms and are used to establish their period to coincide with that of the Sangam literature.

Pandiyan

Among the many coins attributed to the early Pandyas, are a series of punch-marked coins made of silver and copper that are considered to belong to the earliest period. Six groups of silver punch-marked coins and one group of copper coins have been analysed so far. All of these punch-marked coins have a stylised fish symbol on their reverse, which is considered the royal emblem of the Pandyas. On the obverse of these coins are a variety symbols such as the sun, the sadarachakra, the trishul, a dog, stupa etc. The first group of silver coins was found at Bodinayakanur, in a hoard containing 1124 coins all belonging to the same type. The remaining coins in the five silver group and the copper group were all found in the Vaigai river bed near Madurai. Four of the six silver groups have been assigned a date close to the end of the Mauryan rule, c. 187 BCE. Since Thamillakam was deficient in metallic silver and since Roman silver did not become available in abundance until later, around 44 BCE, it has been postulated that the Pandyan kings melted silver from the coins brought in by trade with Magadha or some foreign location other than Rome. The names of the Pandyan kings who issued this series of coins is not clear. Another series of coins, all made of copper and found near Madurai, have the fish symbol on the reverse and among other symbols on the obverse, have the legend Peruvaluthi written in the Thamill-Brahmi script. They have been assigned a date of around 200 BCE and are considered to have been issued by the Pandyan king Peruvaluthi. These coins are representing some of the few instances where the names of Sangam kings appear in non-literary sources. Sangam literature mentions the importance attached to Vedic sacrifices by Thamill kings including the Pandyan Mudukudumi Peruvaludhi. This fact is also corroborated by the discovery of several Pandyan coins that are referred to as the Vedic sacrifice series. These coins have symbols on their obverse that depict the sacrifices, such as a horse tied to the yuba-stambha, a yagna kunta and a nandhipada. More coins with animal symbols such as the tortoise, the elephant and the bull have been found and assigned to the Pandyan kings. Some of them even have a human portrait, possibly of the king who issued those coins, on their obverse. There are also Pandyan coins belonging to the 1st century BCE, that have symbols depicting pearls, signifying the importance of pearl fishery to the Pandyan kingdom. The excavations at Algankulam, near Madurai, recovered two copper coins of the early Pandyas along with Northern Black Polished Ware. These coins have been assigned a broad time period ranging from 200 BCE to 200 CE.

Cheran

Many of the coins assigned to the Chera kings of Sangam age with a portrait and the legends "Makkotai" or "Kuttuvan Kotai" have been found near the Amaravathi River bed in Karur and elsewhere in Coimbatore district of ThamillNadu state. They depict the royal emblem of the Cheras, the bow and arrow symbol, on the reverse. It was generally believed that the Satavahanas were the first indigenous monarchs to issue silver portrait coins. That has been disproved by the discovery of Makkotai and Kuttuvan Kotai coins belonging to the 1st century AD or a little later. Silver coins issued by Augustus and Tiberius have over a period of time been discovered in large numbers from the Coimbatore-Karur region.

Among the Chera coins, the "Makkotai series" bears a unique pattern not found in other Thamill coins of its age. They contain both the portrait of a king (facing right) and a written legend, in this case the word "Makkotai" written in Thamill-Brahmi script. These coins exhibit similarities with the Roman coins of emperors Augustus and Tiberius; like the Roman coins, the portraits on the Makkotai series do not show any jewellery on the king. They are thought to be made of two separate pieces joined by lead, a practice prevalent elsewhere in India at that time. Official seals of the bearing the name “Makkotai” has also been recovered from the river bed; these seals contain the portrait facing left and the legend "Makkotai" written backward (right-to-left). The reverse of the seals is blank. The Makkotai coins and the seals have been assigned a date range of 100 BC to end of 100 AD.

Another aspect of the portraits on the Makkotai coins are that they do not have identical head sizes and some facial features also vary from one coin to another, even though they all have the same written legend. Such an observation has been made of coins assigned to the Western Kshatrapas of Gujarat, which are thought to be another inspiration for the Chera coins. Scholars who analyzed the varying portraiture on the Kshatrapa coins have advanced several theories to explain the phenomenon: that the coins could be of different kings who chose to keep the name of an ancestor on their coins or the coins all belong to one king with portraits depicting him at his different ages. Based on such theories, the Chera coins could either belong to a series of rulers or to a single king called Cheraman Makkotai. Another series of Chera coins depicts various animals along with symbols on its obverse and the Chera emblem on its reverse. Elephant, horse, bull, tortoise and lion are the animals depicted in this series, along with snake and fish. Symbols of inanimate objects include arched hills, battle axe, conch, river, swastika, trident, flowers and the sun.

A few other coins that contain a portrait and a legend have been unearthed; a coin assigned to certain Kuttuvan Kotai with his portrait and the legend "Kuttuvan Kotai" is notable for the occurrence of the "pulli" in the legend. Based on paleography of the script, it has been assigned a date of the late 1st century to early 2nd century AD. A coin belonging to 100 AD with the legend "Kollipurai" and a full-body portrait of a warrior has been assigned to the king Kopperum Cheral Irumporai, as he was known as the victor of Kolli in literature. Another coin of roughly the same period of 100 AD with the legend "Kolirumporaiy" and a warrior portrait has been found; it has not been assigned to a single king, but based on the legend, there are at least six Chera kings who could be associated with it.

A Chera coin with the portrait of a king wearing a Roman helmet was discovered from Karur. The obverse side of the silver coin has the portrait of a king, facing left, wearing a Roman-type bristled-crown helmet. This coin maybelong to the 1st century BC and may be earlier to Makkotai and Kuttuvan Kotai coins. With a flat nose and protruding lips, he has a wide and thick ear lobe but wears no ear-ring. The person depicted appears to be elderly. Unlike other Chera silver portrait coins, the king's portrait on this coin faces left. The coin points to Romans having had trade contacts with the Chera kings and establishes that the Roman soldiers had landed in the Chera country to give protection to the Roman traders who had come there to buy materials.

Archaeological investigations conducted unearthed square or circular Chera coins made of copper from near Cochin. This was for the first time, from a stratographic context, coins of Sangam Chera period have been found in Kerala. The coin, which is almost a square in shape, has an elephant facing to the right and some symbols toward the top of the coin. The symbols could not be identified as the upper part of the coin was partially corroded. A drawn bow and arrow was visible on the other side. Below the arrow is an elephant goad (a prod used to control elephants). These coins bear a striking resemblance to the ones excavated from Karur in Thamill Nadu, said the archaeologists.

Cholan

The number of Chola coins discovered so far are not as many as those of Pandyas; most of them have been found from archeological excavations at Puhar and Arikamedu, and also beds of rivers Amaravathi near Karur and South Pennar near Tirukkoilur. An early Chola coin has also been found in Thailand. The Chola coins do not contain a portrait or a legend and all of them depict symbols of animals and other inanimate objects like the animal series of the Cheras. But, all of them carry the symbol of a tiger, the Chola emblem, on their reverse. One of the coins has been assigned a date earlier than 200 BCE and some others to about the time of Roman influence, which is around the dawn of the Christian era.

Chieftains

Parts of the Sangam age Thamill country were ruled over by several independent chieftains, alongside the three crowned monarchs. Among them, coins belonging to the chieftains of the Malayaman clan have been found in ThamillNadu. Many of them contain a written legend on the obverse and all of them have the image of a flowing river on their obverse. Based on the legends some of these coins have been assigned to specific rulers such as Tirukkannan, also known as Malaiyan Choliya Enadi Tirukkannan, and Tirumudi Kari. A series of coins without a legend but with a horse as the principal motif on the obverse have been assigned to the Malayaman chieftains, because of the river symbol on the obverse. Numismatist R. Krishnamurthy, dates these coins to the period between 100 BCE and 100 CE.

Sri Lankan

Excavations in the area of Tissamaharama in southern Sri Lanka have unearthed locally issued coins produced between the 2nd century BCE and the 2nd century CE, some of which carry Thamill personal names written in early Thamill characters, which suggest that Thamill merchants and Sri Lankan Tamils were present and actively involved in trade along the southern coast of Sri Lanka.

Megalithic sarcophagus burial from Tamil Nadu

Map of ancient oceanic trade, and ports of Thamillakam

Thamilḻakam during Sangam Period

Terracotta statue of Lord Brahma from Arikamedu, Dated between 1st century BCE to 1st century CE

The golden Vimana over the sanctum at Srirangam midst its gopurams, its gable with Paravasudeva image.

The Thamill Chola Empire at its height, 1030 CE

Katar, Tamil dagger which was popular throughout South Asia

Gold coin of Raja Raja Chola I, 985 – 1014, found in Sri Lanka.